|

EN |

||||||||

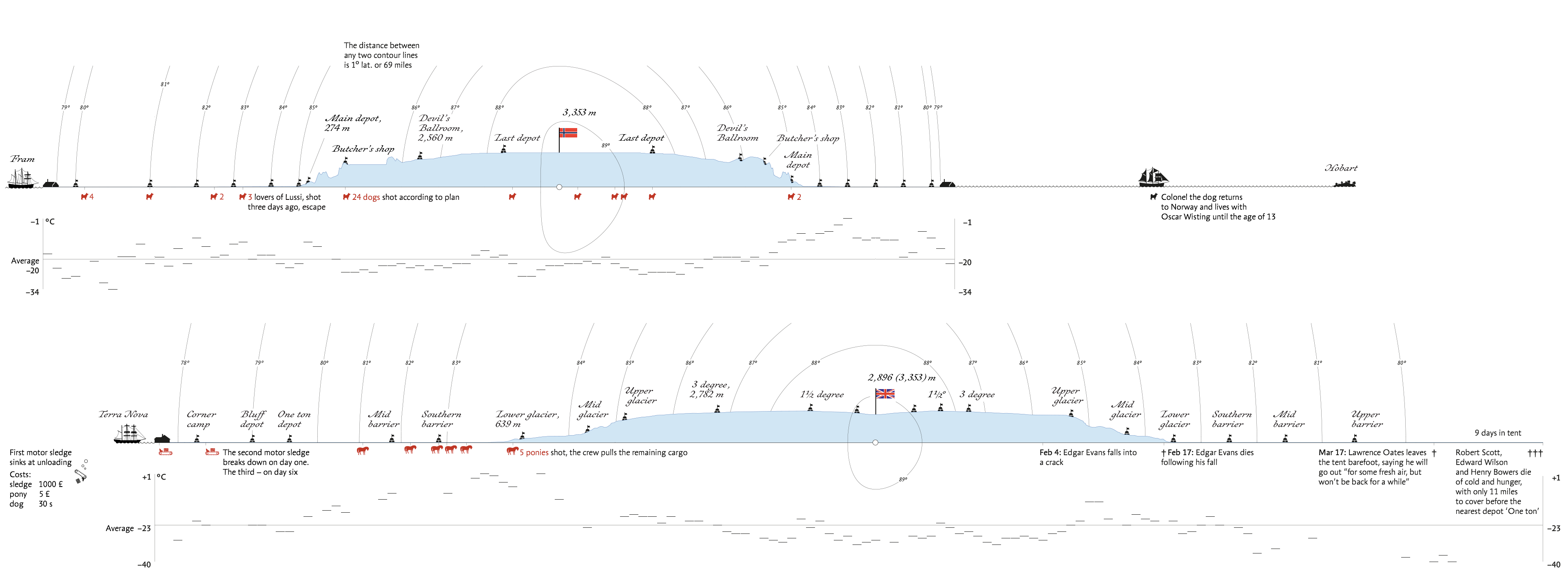

Diagram of Amundsen and Scott’s polar expedition

24th February 2015

|

|

||||

|

On January 17, 1912, after a 78-days-long battle with extreme weather conditions, Robert Falcon Scott’s expedition reached the South Pole – only to discover it had been overrun by the Norwegian expedition of Roald Amundsen 34 days earlier. On their way back, Scott and his party died of cold, hunger and exhaustion, with only 18 kilometres to the nearest food depot. Scott lost his life – and sacrificed the lives of his men – to poor organisation, weak morale and overconfidence. The bureau juxtaposed Scott’s and Amundsen’s expeditions to tribute to the legacy of Polar exploration and help future generations learn from this story. |

|

|||||||

|

“

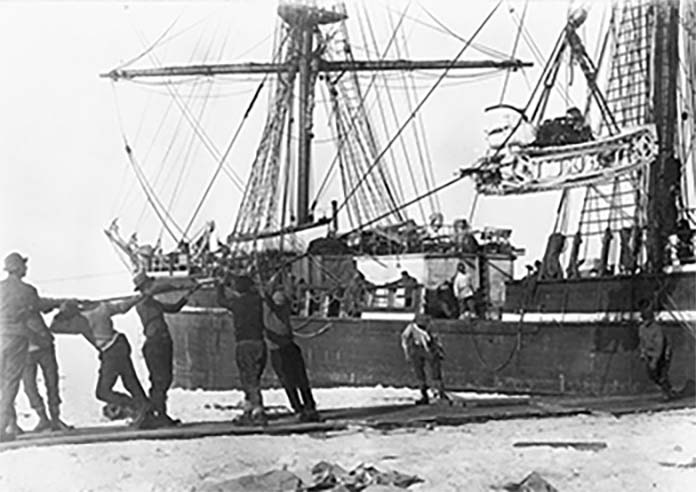

All four forms of transport were mobilized to haul the cargo over the ice from Terra Nova to dry land: dogs, horses, motor sledges The motor sledge was hoisted over the side on to a floe adjoining the ship. Scott then went ashore, leaving Campbell in charge of the proceedings. Shortly afterwards the ice next to the ship began breaking up. 〈...〉 Before a hundred yards, the ice gave way. The sledge broke through and sank into the depths, nearly taking some of the men with it. Salvage was impossible. At the bottom of McMurdo Sound, a hundred fathoms deep, the motor sledge rested, a silent omen. ”“ Amundsen’s landing had been carefully worked out in detail. Each man knew the plan to which Amundsen was working; and therefore could see himself in relation to the whole. The Norwegians knew they had to have their base ready before the end of April, with all seal meat laid in for the winter, and that they were to run three depot journeys to advance supplies to the 83rd parallel of latitude for the Polar dash in the spring. At McMurdo Sound, nobody yet knew what they were going to do because, even after landing, Scott was not sure himself. He had not chosen to take his officers into his confidence. All that remained was rigid unquestioning literal obedience to orders, without regard for circumstances, to which the sunken motor sledge was an outstanding monument. ” |

The British unload the motor sledge. Photo by Herbert G. Ponting

|

|||||

TimelineTraditionally, Scott’s and Amundsen’s expedition are portrayed as lines on a map. This approach is good for showing the parties’ locations: Amundsen’s route was more to the East, while the Framheim base was almost a degree to the South of Scott’s camp. But this approach is useless if you want to compare where each party was at a particular point in time. Chronologically, the routes look identical, like two symmetrical lines to the Pole: |

||||||||||

|

||||||||

|

The expeditions passed each point of their journey twice: as they went to the Pole and back. Before and after the Pole, each expedition travelled at different speeds, depending on the weather and the physical state of the party. When you plot these routes over the map, the way there and the way back merge into a single line. You cannot compare how fast each party travelled. We mirrored the way back and aligned it with the way to the Pole. We got routes of each party from the camp to the Pole and back, laid out on a timeline: |

||||||||||

|

“

On his departure from 82° S., Amundsen carried supplies for a hundred days, taking him to February 6th, 1912. According to his timetable, and based on his performance so far, he would

return to Framheim by January 31st. This meant that even in the unlikely event of missing all depots laid so far, he could still reach the Pole, return to Framheim, turn around, and do

another hundred miles to the south before his food gave out. He had three or four times as much paraffin as he needed. He allowed one day in four for rest and bad weather. He

assumed that he would be forced to Scott, by comparison, had allowed no margin of safety in food, fuel or weather. Simple figures make the point. When Amundsen started, he had three tons of supplies in his depots; Scott had one ton. There were five in Amundsen’s party, making 1,300 pounds per man; Scott started with seventeen men which meant 124 pounds per head. Amundsen had ten times more food and fuel per man than Scott. For Scott to miss a single depot would be fatal. ” |

The Norwegian depot at 83° S. on November 9, 1911. Archives of the National Library of Norway

|

|||||

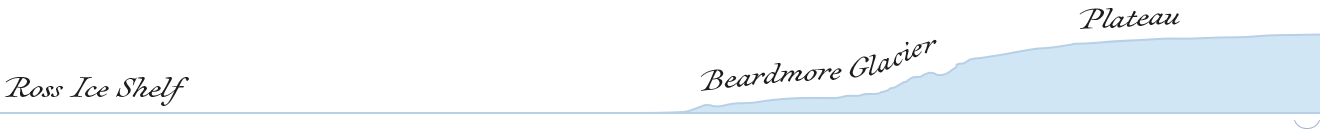

AltitudesBoth parties took similar routes: first along the Ross Ice Shelf, then through the Transantarctic Mountains, and then on through the Antarctic Plateau to the Pole. Scott was familiar with the route: he followed in the footsteps of his predecessor, Ernest Shackleton, who had reached 88° 23′ S. in 1909, with only 111 miles to the Pole. Neither did Scott have problems climbing the well-known Beardmore Glacier.

One day

|

Beardmore Glacier, 1956. Photo by Jim Waldron

|

|||||||

|

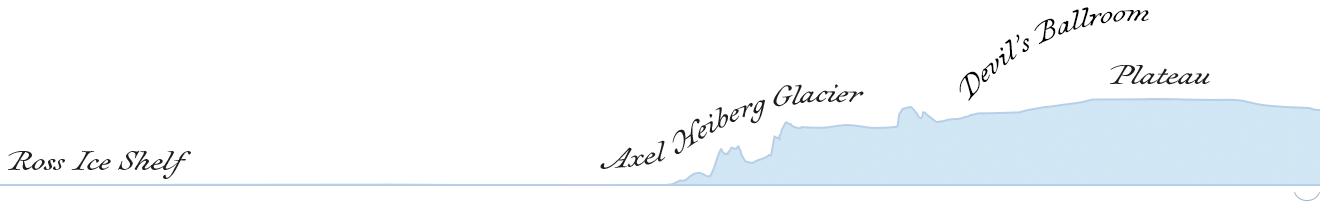

Amundsen and his companions knew little of what was waiting ahead – in a way, they were pioneers. As they climbed the plateau, they faced steep slopes and crevices on the Axel Heiberg Glacier. Faced with fog and bad weather, they called it “The Devil’s Glacier” and “The Devil’s Ballroom.”

One day

|

The Axel Heiberg Glacier, 1956. Photo by Jim Waldron

|

|||||||

|

“

Amundsen's diary: Scott had worn his men out on the climb, without thinking of the return. In any case, by his basic decision to |

Norwegians travelled on skis and in

|

|||||

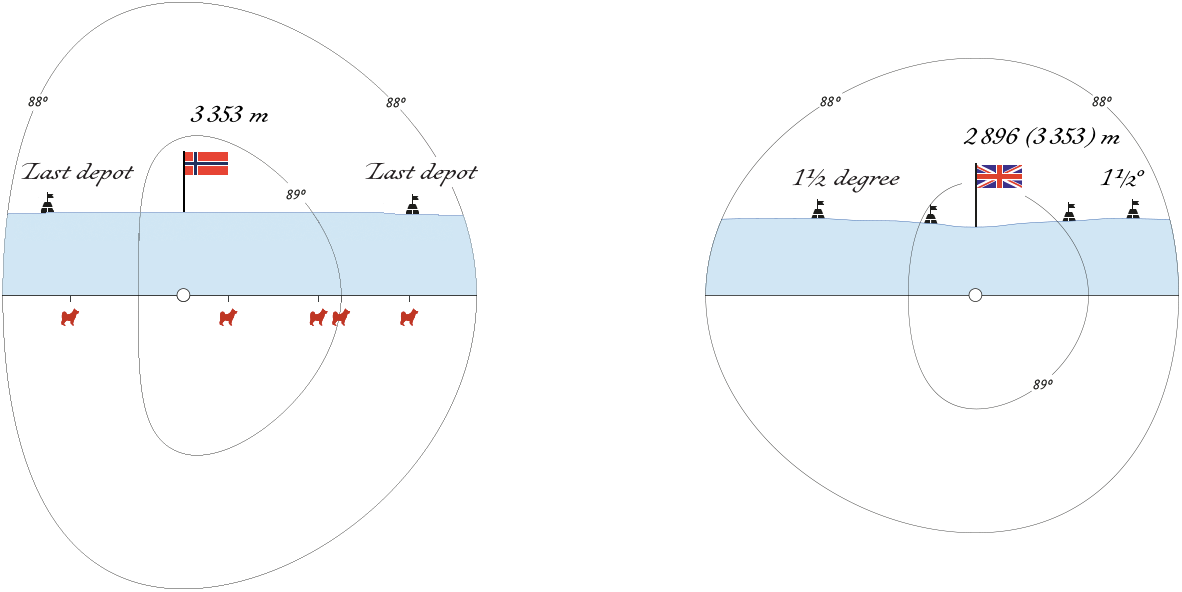

Latitudes and speedThere is a contour line running at each degree of latitude before and after the Pole. Actual distance between each degree of latitude is 69 miles, but our lines are laid out according to the parties’ progress: |

||||||||||

|

The distance between contour lines illustrates the speed at which the expeditions travelled. The smaller the distance, the faster the party travelled in that area; the bigger, the slower. E. g., Norwegians reached the Pole from 88° S. faster: this part of their route is shorter than the one of the British. The British were reaching the Pole slower, but quickly turned back: Scott’s path from the Pole to 88° S. is shorter than Amundsen’s. If we join the contour lines near the Pole, we get what we call ‘jellyfish heads.’ The Norwegian ‘jellyfish’ stretches to the right, the British – to the left: |

||||||||||

Amundsen took his time at the Pole to measure and verify his coordinates

Scott rushed back to be the first to claim the British conquest of the Pole

|

||||||||

|

“

Since December 5th, Scott had been stopped by a blizzard near the foot of the Beardmore Glacier. ‘One cannot see the next tent,’ he wrote, ‘let alone the land … I doubt if any party could travel in such weather, certainly no one could travel against it.’ As it happened, the weather was much the same as that facing Amundsen on ‘The Devil’s Nameday,’ although he was handicapped threefold by the rarefied atmosphere of an altitude of 10,000 feet greater, a temperature fifteen degrees lower, and completely unknown country with no predecessor’s footsteps to guide him. His diary read: ‘It has been an unpleasant day – storm, drift and frostbite, but we have advanced 13 miles closer to our goal.’ 〈...〉 But Scott, unlike Amundsen, had cut things fine. In his own words, ‘we can’t afford’ the delay. In a journey of four months, he had not allowed for four days’ bad weather. At the most, said Bowers in his diary, ‘the delay will mean nothing worse than a little short commons on our return journey, a trifling matter’. ” |

The British

|

|||||

DetailsThe icons and diagrams resemble actual places and objects: |

||||||||

Fram, schooner

Crew: 19

Length: 38,4 m Width: 10,6 m Deadweight: 440 t Engine: diesel, operated by one crew member |

Terra Nova, barque

Crew: 65

Length: 57 m Width: 9,4 m Deadweight: 747 t Engine: steam, coal-fueled, operated by 2-3 greasers |

|||||||

Framheim Base Camp

“Framheim resembled a whole little village rising out of the snow. Fourteen

At Framheim, everybody lived together in an atmosphere between that of a mountain hut and a sealing ship”. |

The British Base Camp

“Cape Evans, on the other hand, was a hybrid of warship and academic common room. The hut was divided across the middle by a partition of packing cases. On the one side, the

officers, scientists, and

|

|||||||

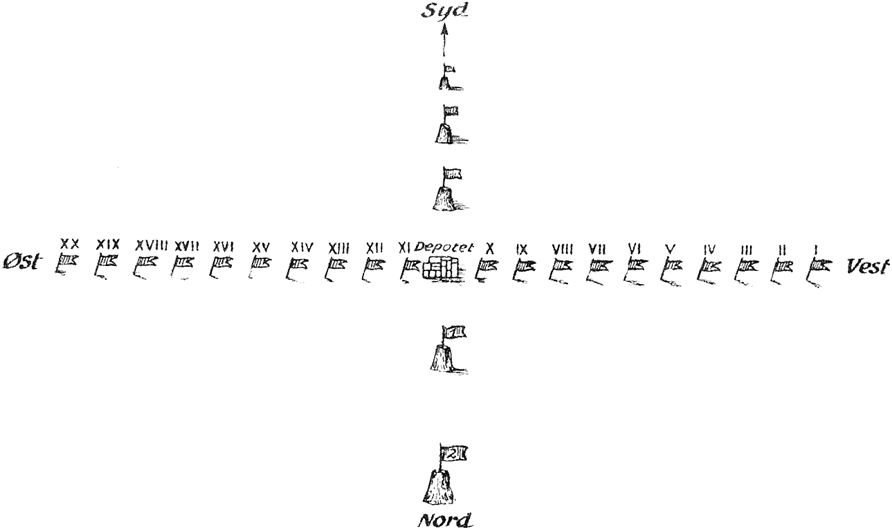

Illustration by party member Torvald Nielsen

“The method he adopted was a line of black pennants on short sticks running

|

The “One Ton” depot. Photo by Robert Scott

The British Depots

“Finding each depot now became a crisis, because there were none of Amundsen’s ingenious transverse markings, but merely a single, inadequate flag. Cairns were too low, badly

made, and too few for navigation. Scott depended on his outward tracks to find his way back”.

|

|||||||

Helmer Hanssen and the dogs. Archives of the Norwegian Polar Institute

Dogs

Amundsen's diary:

“11th February: The dogs pull magnificently, and the going on the barrier is ideal. Cannot understand what the English mean when they say that dogs cannot be used here. 15th February: A fine performance of our dogs this: 40 geographical miles yesterday – of which 10 miles with heavy load and then 51½ miles today – I think they will hold their own with the ponies on the Barrier.” |

Scott’s expedition. Archives of the Natural History Museum of London

Ponies

“Scott was soon initiated into the drawbacks of ponies in the Antarctic, when they broke through the sea ice or wallowed up to their bellies in snowdrifts. The dogs showed their

insulting superiority by such diverse exploits as charging enthusiastically with a full load over polished sea ice in pursuit of a whale that had surfaced in a lead, and efficiently

scampering over powdery drift and grainy crust for mile after mile”.

|

|||||||

|

“

Slowly the speck turned into something that moved, and then they were standing under the black flag of disillusion. Dog stools and paw marks in the snow told their simple tale. The pitiless wind in their faces seemed colder than an hour before. 〈...〉 Scott wrote gloomily in his diary: ‘The Pole. Yes, but under very different circumstances from those expected. We have had a horrible day – add to our disappointment a head wind 4 to 5, with a temperature −22°,

and companions labouring on with cold feet and hands … Great God! this is an awful place and terrible enough for us to have laboured to it without the reward of priority. 〈...〉 In other words, Scott was still hoping for a kind of victory. He did not yet quite grasp that the return was going to be a fight for survival, although he did understand that there was no time to be lost. ” |

Robert Scott, Lawrene Oates, Edward Wilson and Edgar Evans near Amundsen’s tent at the South Pole. Photo by Henry Bowers

|

|||||

Margin of safetyThe story of Scott and Amundsen teaches us to always plan with a margin of safety. The difference between how the expeditions were planned: |

||||||||

You don’t need to be a member of a polar expedition to follow this rule. When you plan without a margin of safety, you predictably fail in life and project management. If you are going out of town for five days, it’s wise to grab six or seven pairs of socks. What if your feet get wet? If you have just enough gas to go there and back, why not top up the tank, just in case? What if your tire runs flat, and you’ll need to spend hours waiting for a tow truck at −20° C? If you are a manager prepping for a project with a recently-hired designer, have a quick replacement at hand. What if the newbie panics two days into the project and leaves? If you are a designer working with an art director, remember that you might be asked to start from scratch. To avoid this fate one night before the deadline, show your work to the art director as early as possible, and reserve enough time to redo the work. If you are a developer, add a couple of days to test your product and fix bugs. What if your front-end glitches in some browsers? Planning without a margin of safety is idealistic and short-sighted. It leads to irresponsible promises to clients. Naïveté always results in suffering, losses and conflicts. |

Scott’s party daily diet: cocoa, pemmican, sugar, biscuits, butter. Photo by Herbert G. Ponting

Pemmican is a nutritious and slowly digestible meat concentrate used in military campaigns, hunting parties and polar expeditions |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

“

Scott would have to answer for the men he had lost. Shackleton would have the last laugh. That was something Scott could not face. It would be better to seek immolation in the tent. That way he could snatch a kind of victory out of defeat. Wilson and Bowers were persuaded to lie down with him and wait for the end, where the instinct of other men in like predicament was to keep going and fall in their tracks. For at least nine days they lay in their sleeping bags, while their last food and fuel gave out, and their life ebbed away. 〈...〉 When Amundsen’s and Scott’s first reports reached civilization, a Norwegian newspaper remarked that Amundsen... leaves the impression that it was all basically a comparatively simple affair [while] Scott brings out and underlines the ‘inhuman exertion’... ‘the tremendous dangers’... ‘the exceptional ill fortune’ and the ‘unsatisfactory weather’ both when it froze and when it thawed. This was fair comment. Scott wanted to be a hero; Amundsen merely wanted to get to the Pole. Scott, with his instinct for |

The grave of Scott, Wilson and Bowers. Photo by Herbert G. Ponting

|

|||||

Sources and referencesData on key altitudes, temperatures, depots, dogs and ponies sourced from the expedition logs of Amundsen and Scott. Parts of landscape elevations not found in the diaries charted with the 2013 Google Earth data. Quotes on this page are from Roland Huntford, “Race for the South Pole: The Expedition Diaries of Scott and Amundsen”, unless specified otherwise. The writing on the chart done in Voltaire.

|

Bin |

||||||||||